As of September 2018, I’m working on a PhD research that revolves around ecological movements, imaginaries of water, and relationships between humans and nonhumans in the diverse contexts of Ecuador and the Netherlands. What is this research about?

Continue reading Research project: Imagining WaterDutch dikes, water, and the wizards who master it

Although the Dutch social imaginaries of and discourses on water are not a univocal, it is univocally stressed that Dutch history, the landscapes, democratic institutions, ‘modern civilisation’, and supposedly the political culture of seeking compromises, are all unthinkable without the ‘battle against the water’ throughout history and the thereof emerging technologies, mega-constructions such as the Delta works, and institutions such as the water boards (Van den Brink 2007, Van Dam 2000). Approximately fifty percent of the country today lies below sea level, and almost the whole Dutch landscape is human-made from the Middle Ages onwards. A vicious circle of human response to increasingly frequent flooding kept changing the landscape with more and stronger dikes (Van der Vleuten & Disco 2007). The technology to separate land from water developed from ditches, dikes and sluices to windmills and pumping stations and eventually the megastructures of large dams and storm surge barriers. All these constructions have intensively recreated the Dutch landscape, to such an extent that there is an internationally famous cliché that ‘God created the earth and the Dutch created the Netherlands’ (Ten Brinke 2007).

Whilst every young Dutch citizen learns about the homeland’s water history in school, which is presented as something to be proud of, nowadays water is hardly a topic of real concern in everyday life. Water as a ‘threat’ is seen as something of the past, in the consciousness of most Dutch people at least. The hydraulic engineers and water authorities make sure of that. Even more so, water almost seems to be taken for granted, not just by myself but by many other Dutch inhabitants. Clean drinking water runs from the tap, the shower, and even the toilet. Drinking water, water to sprinkle the garden, and water to swim in or sail on, the ‘nice sorts’, are always abundantly available, whilst the ‘nasty sorts’, in the form of storm surges, waste water, or heavy rains, are conveniently kept from us or dealt with by water professionals and technologies. We do not have to worry about it, and we indeed do not.

The Dutch social imaginary of water seems to be engrained with pride of the water engineering ‘superiority’ of the Dutch in the world, as well as a deep trust in these engineers’ skills in keeping us safe and arranging fine drinking water for all inhabitants. This pride of and trust in the water engineers resonates in my own imagination of water, too, that is nourished by the way my grandmother talks about De Ramp (the disaster) of 1953, in which the dikes of the province of Zeeland broke during an immense storm surge. Seawater flooded the polders and in one week 1.835 people drowned and more than 750.000 inhabitants were affected (Bijker 2007). After De Ramp, the Oosterschelde storm surge barrier was constructed, a megastructure that is open under normal circumstances but can be closed when s storm surges is forecast. The thing is promoted worldwide as a technological wonder, and advertised as “the eighth modern wonder of the world” (Van der Ham et al. 2018), constructed by the Dutch “water wizards” (Van der Vleuten & Disco 2004).

In the midst of the disaster, my own grandparents and their family had to flee to Tilburg, where they lived with a host family for six weeks, because the water came all the way to our village. As a child I was often intrigued by my grandmother’s stories. For her, the sea had literally threatened her life, forever impacting her relationship with water and always proud at ‘our’ dikes and other structures. When she only recently visited the museum near the Delta works with my mother, she turned emotional again whilst seeing the videos of the breaking of the dikes, even after more than sixty years. Through listening to her stories, my grandmother’s relation with water must have seeped through generations.

The Dutch water history is constantly and proudly reproduced by politicians: they point at the Dutch ‘tradition’ to find compromises through the ‘polder model’, rooted in the first water boards, and promote the Dutch water expertise worldwide as an export product. By this continuous reproduction of pride, the Dutch-water relation arguably becomes deeply engrained in people’s shared imaginaries and sense of nationality. This imaginary then again finds its way in new plans to master the water, for example in the construction of new islands in the IJsselmeer, of building new land to expand the port of Rotterdam, and to design large off-shore windmill parks. The Dutch relation with water seems to manifest itself merely through their relation with water technology, rather than with water in itself.

Considering the Dutch history with water, it is at least curious that many present-day ecological movements also (almost) seem to take water and water technologies and infrastructures for granted, at least as they play out in the Netherlands. Although off-shore windmill parks harm marine ecosystems, most large ecological movements praise the renewability of wind energy, also in offshore parks, as a good constituent for fossil fuel. There is also no conspicuous ecological protest against the repairing and strengthening of dikes and pumping of the water, nor against ‘building new nature’. In fact, Dutch ecological movements that revolve around water-related ecological damage or conflict, or about water in general, are pretty rare. There are the well-known Plastic Soup Foundation and Ocean Clean-up, organisations that aim to raise awareness on the large negative effects of plastic waste on the oceans and marine life, and to reduce plastic consumption. These organisations are not targeting the Netherlands only, but the whole world. They can afford to: Dutch beaches are not as filled with waste compared to the Indonesian beaches. Telling is also the example of response to earthquakes in the province Groningen that occur because of drilling for natural gas. The dikes surrounding Groningen at the coast are damaged because of these earthquakes. Whilst thousands of Groningen inhabitants are struggling with the gas company for financial compensation and repair of their dwellings, the water boards immediately received large amounts of money to repair and strengthen the dikes along the coast. This is not questioned nor contested by activists who support the Groningen people. It is seen as a priority. The simple explanation for this apparent lack of water movements are: we need strong dikes because otherwise we would all drown; wind energy is more ‘sustainable’ than fossil fuels; new ‘nature’ in the IJsselmeer is good for birds. More complex explanations could lie in a relation with and imaginary of water shaped by a hierarchy in which humans are superior to the rest of the ecology.

However, at least one interesting movement to focus on for this research might be the Parliament of Things and the Embassy of the North Sea, established in 2018. The Parliament of Things is an open space for conversations between humans, things, animals and plants, based on the book We have never been modern by Bruno Latour (1991). In the summer of 2018, as spin-off of the Parliament of Things, the Embassy of the North Sea has worked on a plan for the years until 2030. Their strategy consists of imagining, connecting, and representing. It uses imagination as a catalyst of revising relationships with the North Sea and to develop alternative scenarios for the future. It aims to give a political voice to nonhuman North Sea stakeholders and researches relations and forms new ecological movements. The movement’s website notes: “We live together with the sea. She fascinates and nourishes us, once we emanated from her. At the same time, we feared and subdued this great mirror of our land. The sea always stirs, in many ways.” The movement wonders what, nowadays, is our relations with “our largest public space”. Its vision is described as follows: “The North Sea belongs to herself. In the Anthropocene, new forms of imagination, connection and representation are needed to see and understand the North Sea in all her diversity. The Embassy of the North Sea unites, in urgent and ingenuous manners, humans and non-humans in and around the North Sea. Building more inclusive sea-perspectives, the Embassy of the North Sea investigates whether the North Sea must be an independent legal person.” This type of reasoning intends to resonate the anti-anthropocentric ideas and at the same time challenges us to re-imagine our relation with the sea, by using all of our senses.

Imagining in the Anthropocene

How do people imagine water, how did they do so historically, and what does that mean? René ten Bos (2015) argues that people seem to take water and its life-giving characteristics for granted, or ignore it. Especially in western thinking, he argues, water has long been ‘objectified’, not seen as something with intrinsic value, but only as something ‘out there’ that humans can use or must control. Imaginaries revolving around water seem to link to a certain human relation to water, and the nonhuman world in general, in which water and other things of the earth are ontologically reduced to being resources, commodities, external supplies, that can be measured, tamed, mastered and/or used by humans. In such a way of thinking, it is overlooked that water is a fundamental part of life on earth and literally a large part of ourselves. This denial, indifference, or downplaying of water’s importance arguably allows for a way of treating it – and the nonhuman world in general – that is only utilitarian and hierarchical: humans above the rest. With such a way of thinking, the step towards doing ecological harm, unintentionally or carelessly, is easily taken, allowing for damming rivers, for dumping waste and chemicals in the ocean, if only it is benefitting or convenient for human beings. Scholars argue that this social imaginary of water, its reduction to its utilities, is one of the root causes of ecological disaster that we need to challenge and question (see for example Ten Bos 2015; Neimanis 2012, and the recent IPBES[1] report 2019).

This idea about water and the controllable ecology has plausibly already been dominant, at least in western thought, since the ancient Greek philosophers and came even more into fashion since the industrial and scientific revolution. Although one of the first European philosophers, Thales of Milete, did coin that water is the primary element that all life begins with, since Socrates and Plato water has not been (philosophically) referred to as the fundamental principle of life (Ten Bos 2015). Since then, western philosophers and thinkers seem to have “attempted to grasp solid ground”: flow and liquid seemed to be too dangerous and dynamic, we cannot rely on it. In this time, bodily senses and the imagination became inferior to the use of logos (ratio) whilst philosophising. In the seventeenth century, senses and imagination in philosophical thought got an even lesser status (Sepper 1989). With the dualist ideas of René Descartes, a binary way of thinking bloomed that conceptually separated the body from the mind, nature from culture, emotion from ratio, and humans from nonhumans (Huggan & Tiffin 2007, Leiss 1994). Descartes argued that the mind is superior over the body, because that is where reason is located, whereas in the body only passion and irrationality are found (Culhane 2016). Following Descartes’ philosophy, the idea became popular that using ratio and critical thinking offers us the best way of knowing the world, and the imagination only distract us from fully comprehending it (Sepper 1989).

Humans in large parts of the world started to believe that we could know, control and use everything in the world by using rational thought. With the invention of the steam engine and the industrial revolution, these ideas of measuring, using and exploiting nature became practiced, amongst other things (but not solely) in the massive extraction of resources for the processes of production. From this revolution onwards, water literally became the lubricant for industrialisation, urbanisation, and agricultural intensification, all processes that required enormous amounts, secure supplies, and fine qualities of water (Bakker 2012). Whilst people had long been using and manipulating water by irrigation systems, redirecting streams and creating water mills, the increasing demands for water in the industrial revolution, the growth of capitalism, and urbanisation – processes that embarked in the seventeenth century and accelerated over the next two hundred years – were of an unprecedented order (Linton 2010).

Not only in relation to water but more generally as well, in the industrial revolution human beings started to change the globe decisively, to such an extent that it marked a turning point in history: the beginning of what scholars widely agree to be a new epoch called the Anthropocene. In this epoch, human beings are directly and indirectly impacting the world unprecedentedly and permanently to such an extent that it is leading to global warming, biodiversity loss and other environmental crises (Crutzen 2002, Zalasiewicz 2013, Lewis & Maslin 2015). There is large scholarly consensus that due to the accelerating use of fossil fuels and rapid societal changes, the industrial revolution marks the Anthropocene’s beginning[2] (Crutzen 2002).

Contested imaginaries

In present times, the urge to ‘do something’ against or mitigate ecological crises is not only felt by scientists but also by many (but far from all) citizens and politicians. According to Anna Tsing, humans started to become aware that they could destroy the liveability of the planet after the bomb on Hiroshima: grasping the atom was “the culmination of humans dreams of controlling nature. It was also the beginning of those dreams’ undoing” (2015: 3). This ‘undoing’ surfaces in the rapid increase of climate marches and student protests (New York Times 2018), investments in technological innovation, climate policies and international treaties (United Nations 2015).

However, thinking of ‘nature’ as usable and controllable for human benefit remains dominant. Infinite economic growth and progress remain the ultimate aims of most states. Politicians, technocrats and scientists attempt to measure effects and predict the impact of current and future environmental crises. They seem to be convinced that better measurements, more efficient use of water and other ‘resources’, and technological solutions will solve the problems (Raworth 2018). Economic growth ought to be a prerequisite to be able to invest in such innovations, and in this logic, consumption and production must continue to increase too (Raworth 2018). The ideas that humans are superior over nonhumans, that water must be tamed and controlled for human’s most efficient use and protection, and that economic growth is crucial for society’s welfare, remain the dominant discourses.

A paradox emerges here: one the one hand, societies are aiming for economic growth as priority, and on the other hand, that growth must be ‘sustainable’, ‘as much as possible’ (source). The paradox, or double-bind (Bateson 1972, Eriksen 2016,), lies in that economic growth inherently requires an increase of production, consumption, energy-use and resource extraction. ‘Sustainable growth’ – often implied by politicians and international institutions like the Sustainable Development Goals – can be called a hoax: ‘economic growth’ and ‘sustainability’ are two inherently incompatible things. Scholars as well as environmental movements therefore suggest that current and future ecological crises are not simply solvable by technological innovations, better measurements, and political policies without breaking with a focus on perennial economic growth, ideas of progress and a rationality of measuring and counting everything, that are dominant in western thinking (see for example Eriksen 2016; Escobar 1995, Acosta 2016, Gudynas 2011).

In the words of Tsing (2015) and Buell (1995), the ecological challenges we are facing today are related to the way we imagine the ecology. Both argue that environmental crises and Western thought are intrinsically interwoven. Buell stresses that “…western metaphysics and ethics need revision before we can address today’s environmental problems. [The] environmental crisis involves a crisis of the imagination the amelioration of which depends on defining better ways of imagining nature and humanity’s relation to it” (1995: 2). Neimanis (2012), in line with Tsing and Buell, wonders how ‘really’ paying attention to water – how it moves, what it does, what it is threatened by, how it organises itself and other bodies – makes her and other people to treat water better. Raworth (2018) suggest that in order to do that, we must ‘unlearn’ the capitalist economic rationales of infinite growth, measurements of GDP as ‘welfare’, and the ‘invisible hand’ of the market. What we need, these scholars imply, is a radical, new way of thinking about human’s place in the world at large, a turn from the discourse of Descartes’ fashion that separates humans from the rest of the earth and all the living and non-living beings in it. We must, they say, problematise ‘anthropocentrism’, that is, the paradigm in which human beings are believed to be the most important beings of the planet.

[1] The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) is a renowned international institution which assesses the state of biodiversity and of the ecosystem services it provides to society. Its reports are approved by 130 governments.

[2] Timothy Morton (2016), amongst others, notes that the Anthropocene already has its roots ten thousand years earlier, with the invention of agriculture. The nature-culture split is the result of a nature-agriculture split, he states (Morton 2016: 43).

Sources

Acosta, A. (2016). Buen Vivir, Latijns-Amerikaanse filosofie over goed leven. Ten Have, Amsterdam.

Buell, L. (1995). The environmental imagination. Thoreau, nature, writing, and the formation of Americanculture. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Crutzen, P.J. (2002). Geology of mankind. Nature, 415.

Culhane, D. (2016a). Imagining: an introduction. In Elliot, D. and Culhane, D. (editors). A different kind ofethnography. Imaginative practices and creative methodologies, pp 1-21. University of Toronto Press.

Culhane, D. (2016b). Sensing. In Elliot, D. and Culhane, D. (editors). A different kind ofethnography. Imaginative practices and creative methodologies, pp 1-21. University of Toronto Press.

Eriksen, T.H. (2016). Overheating. An anthropology of accelerated change. Pluto Press, London

Gudynas, E. (2011). Buen Vivir: Today’s tomorrow. Development. 54:4, pp. 441–447.

Huggan, G. and Tiffin, H. (2007). Green postcolonialism. Interventions, 9:1, pp. 1-11.

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (2019). GlobalAssessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Retrieved 26 June 2019 from https://www.ipbes.net/global-assessment-report-biodiversity-ecosystem-services

Leiss, W. (1994) The domination of nature. McGill Queen’s University Press, Montreal & Kingston, Lewis, S.L. and Maslin, M.A. (2015). Defining the Anthropocene. Nature, 519, pp. 171-180.

Linton, J.I. (2006). What is water? The history and crisis of an abstraction. Doctoral thesis, department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Carleton University.

Morton, T. (2016). Dark ecology. For a logic of future coexistence. Columbia University Press, New York.

Neimanis, A. (2012, May 25). Thinking with water: an aqueous imaginary and an epistemology of unknowability. Paper presented at Entanglements of new materialisms conference, Linkoping, Sweden.

Tsing, A.L. (2015). Mushroom at the end of the world. On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Sepper, D.L. (1989). Descartes and the eclipse of imagination, 1618-1630. Journal of the History of Philosophy, 27:3, pp. 379-403.

Ten Bos, R. (2015). Water. Boom uitgevers, Amsterdam.

Zalasiewicz, J. (2013). The epoch of humans. Nature Geoscience, 6.

What is water?

In my doctoral research I dive into water. But what are we actually talking about when we speak of water; what is water? I can imagine a river, a lake or an ocean, rain or the liquid that pours from the shower, that fills the bottles I take with me every day, or the pool I swim in. Or it is simply the famous H2O?

Continue reading What is water?El Paro: national protest in Ecuador and framing in the media

This week, I have experienced the specific scent and feel of teargas for the first time. It is in first instance itchy, as if someone put pepper in your nose and eyes. Then it starts to hurt. You cannot breath normally and you start to cry. You want to run away, preferably to the nearest fire. The smoke helps, but it takes time before you’re back to normal. That stuff is not innocent, like you often hear on the news about protests, mostly elsewhere in the world. It doesn’t kill initially, but it does make people blind. It creates panic and people start running in all directions, falling over each other. The police in Ecuador is currently using a lot of teargas.

Initially I intended to write a blog about the climate strike that was organised in Quito on the 27th of September, the day that worldwide people took the streets for “greener” policies and measures of governments and companies. I wanted to write about the reasons why many of my Ecuadorian friends involved in a social-ecological movement were not joining the strike. “It’s organised by people with comfortable lives in rich countries, who are forming the biggest threat to our planet”, was what they told me. It confused me initially, to be honest, because why would they not go to strike for a cause they shared, only because the initiators of the strike are from rich countries? A few days later, whilst writing about the relatively small number of people that showed up (about a thousand), and pondering about why my friends had not joined the strike, I received a message that the city centre was in chaos because of protests. I went outside to have a look, a few-minutes-walk from where I live. That was the 3rd of October and only the beginning.

“Fuera Lenín, Fuera!”

Thousands and thousands of people are on the street. Taxi’s and busses have blocked the main road. Teargas hits my nose and eyes, even from a safe distance. People are scanting “Fuera Lenín, fuera” (away with Lenín Moreno, the president) and spraying “Mierda FMI” (Shit International Monetary Fund, IMF) in graffiti on the walls of the closed shops. People are making fires on the street and others are selling sigarettes, both help against teargas, as I learn. Around the corner I can see confrontations with the police further down. I’ve never seen a mass like that, and so furious. The police uses teargas in order to prevent the protesters from going to the palace, where the president is seated, they respond by throwing stones at the police. The government announced a state of exception for sixty days.

The motivation: a stop on fuel subsidies. This might be an example of a “green policy” that was demanded by the climate strikers worldwide last week, but people here are furious and scared. The stop on subsidies is part of a list of measures, announced by President Lenín Moreno a few days earlier, to “improve the Ecuadorian economy”. The budget cuts are ordered by the International Monetary Fund in exchange of a loan. The measures hit people hard, especially the poor who could already hardly get by when the subsidies were still in place. Because of the higher fuel prices, transport and foodprices have increased to such an extent that people cannot afford it anymore.

Actually, this was only the trigger, the so-called last straw that broke the camel’s back. People are angry at Moreno and his government, that in their eyes only enriches its capitalist self, elite classes, and foreign companies. The administration threathens the land of indigenous peoples by giving out mining and oil concessions, even though Moreno in election time promised not to. The fact that the USA military is allowed a basis at the Galapagos Islands, plus the orders by the IMF, is perceived as that the country is sold out. I’ve spoken with many people who feel threathened in their security, not only by the economic measures, but also by enormous police and military agression in the last days.

Framing and censorship in the media

I find it frustrating that international news media are scarcely and/or inaccurately reporting about the events in Ecuador. One of the first messages I read were written by the Dutch NOS and Algemeen Dagblad, reporting about some tourists that are stuck and that it’s better not to travel here. It embarasses me. Overall, Ecuadorian and international news media predominantly report about“violent protests” and “vandalists” destroying the city. We read about the “economic damage” of the unrest, and that the government is “open for dialogue”. Although (most of it) is not ontrue, it is framing the events in such a way that the protesters are “criminals”, even “terrorists” who destroy the country and don’t want to talk.

and “I’m open to dialogue”. Source: Facebook page Movimiento Vientos del Pueblo.

We do not read in de media that the police is incredibly aggressive, and violently cracks down on peaceful protesters. The fact that the police intruded a university buidling, used as a refuge for indigenous people who came from the countryside, throwing teargas where old people and women with children were resting, unable to leave the building, remains unreported. Violence by the protesters (that is, only some of them) means fighting by hand, throwing stones found on the street and throwing back the teargas units where they came from, for self-defence. Violence by the police means throwing teargas not only to the frontlines but in the crowds with bystanders too, it means rubber bullets, tanks and armored cars through the streets. Once I was witnessing things from a very safe distance, I thought, close to where children were playing in the park. But suddenly I saw about thirty police officers on motorbikes entering, hunting down the people through the park. There are at least 7 deaths, amongst whom an indigenous leader and a child, more than 500 injured, and more than 700 people in jail without any trial.

Ecuadorians are forming one big block

I have spoken to dozens of people, from die-hard protesters to people on the street who try to avoid the unrest to go to work, and bystanders, shop owners, my neighbours, taxi-drivers, scientists. I haven’t met a single person who is pro Moreno or against the protests. “La rebellión se justifica”, they all say: the protests are justified, and the president must go. President Moreno’s statement that he is open for dialogue is widely questioned. He has announced not to be willing to change the measurements, and not giving in to “terrorists”.

It is generally known amongst the Ecuadorians that mainstream media are not to be trusted. Instead, a system of civilian “journalism” has been set up through Facebook and Twitter. People forward videos of what happens throughout the country, also at the frontlines of the protest. Which roads are free to go and which ones are blocked is shared on social media platforms. There are posters of “how to prepare against teargas?” and about where and when in the city indigenous people will arrive from the countryside to join the protests, and about people who are wounded by police violence.

At the time of writing, the 9th of October, the largest protest so far has been announced. CONAIE, the national organisation for indigenous people, says that about 40.000 indigenous people have come to Quito to join the protests, and more will come. This morning I woke up by the sound of helicopters. The view over the city is blurred by smoke. Teargas is reaching my terrace. I had never experienced it before, but that smell and feeling is so specific that I will never forget it. In the past week it has become clear to me why my ecologist friends did not join the climate strike: there will simply be no ecological justice without social justice.

To be human is to be sexual

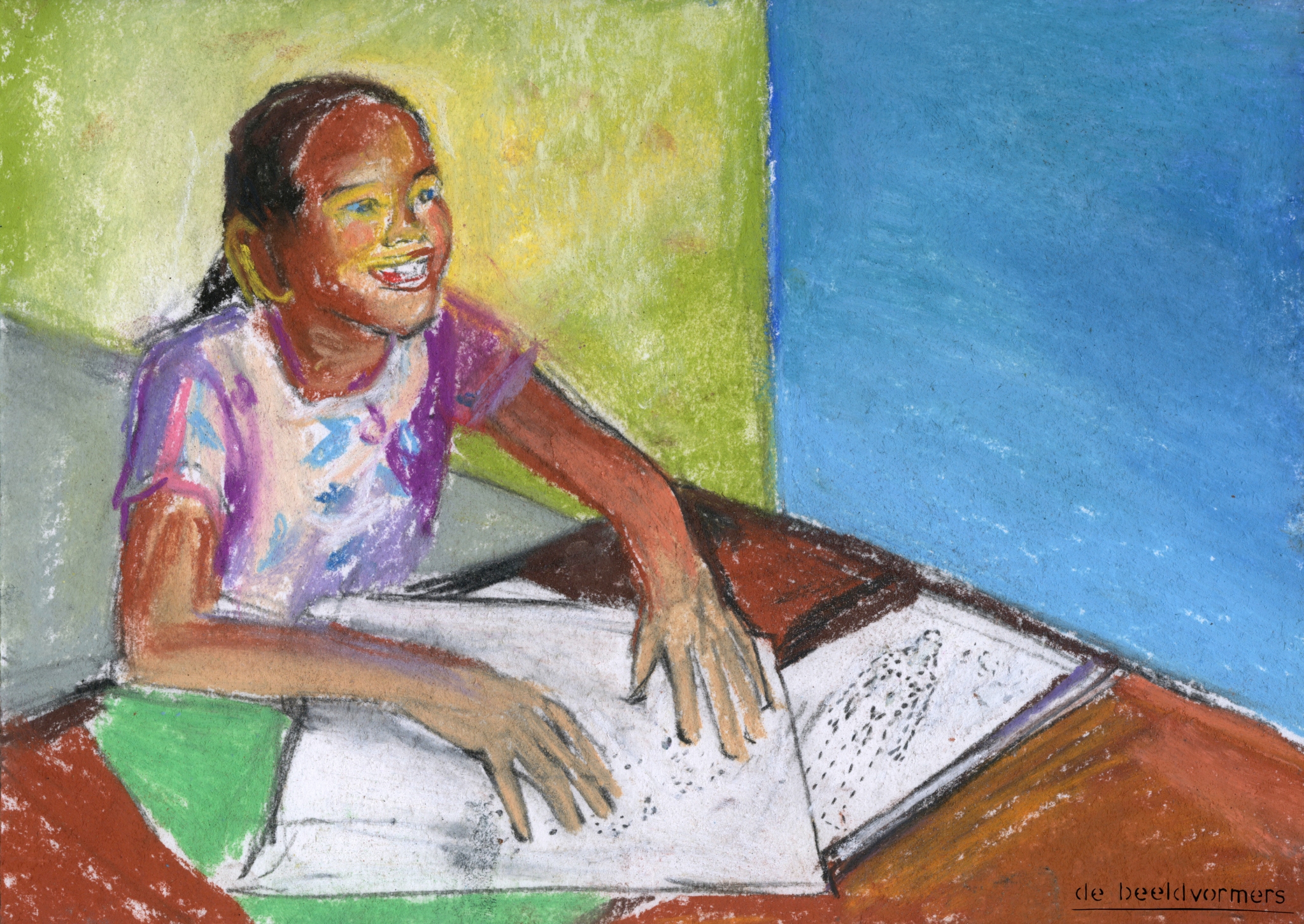

Illustrations are made by De Beeldvormers.

“I am blind, and so is love. Get over it!”1

“I’m here. I’m disabled. And I do it. Yes, I do. Even in this body that you can’t imagine anyone doing it with and loving.”2

“I get the feeling people think that because I am in a wheelchair there is just a blank space down there.”3

“Some people misunderstood our relationship, and thought of him as being my caregiver instead of my partner”4

“People would say to me: ‘Why would you want to be tested for HIV? As if you’re able to have sex!”5

“Why do we think that someone who only has one hand would not masturbate with the other? Or that someone who cannot see does not paint her own mental images of the perfect lover?”6

“First I am a woman and second a person with a disability. I deserve to have a partner, children and a family.”7

“Sexuality is not just physical – it is also socio-cultural, spiritual, and psychological. Everyone has the right to sex education that encompasses all of these aspects.”8

Just like all human beings, people with a disability are sexual. Those with disabilities are, first and foremost, people: they have the same rights, feelings, sexual desires, needs and possibly family dreams as anybody else. A positive body image and healthy self-esteem helps in pursuing and celebrating a pleasurable and healthy sexual and family life. At the same time, it is necessary to know how to set boundaries and how to protect against sexually transmitted diseases, unwanted pregnancy and in the worst case, sexual violence. In other words: all people – both male and female – with or without disabilities have the same needs in terms of access to and information about ‘sexual and reproductive health and rights’: SRHR, so that they can celebrate satisfying sex and having a family if, when, and with whom they want.

This should be needless to say. However, the SRHR needs of people with disabilities often remain unmet. A profound worldwide misconception exists, that suggests people with disabilities are either asexual or hypersexual (without inhibitions)9. In terms of love, relationships and having children, it is thought to be best if men and women with disabilities do not venture into these areas, for their own sake and that of society. With the imposition of such negative ideas, and telling them they are undesirable and not worthy of desires, it is likely that the self-esteem of people with disabilities is suppressed. As a result, they might not seek access to SRHR services of their own accord10.

Not only disability, but sexuality too is unmentionable in many cultures and is often shrouded in shame. In many societies, it is taboo to openly discuss issues like menstruation, relationships, sexual diversity, safe and pleasurable sex and family planning11/12. This is even more so when it comes to sexual exploitation and abuse, let alone when people who have a disability are involved.

Due to the above-mentioned negative perceptions, people with disabilities are more likely to experience the downsides rather than the upsides of sexuality and family life than others. Whilst more research and data are needed, the figures below highlight some of the key issues from recent studies related to SRHR and disability:

People with disabilities are as sexually active as their non-disabled peers13;

People with disabilities are twice as likely to be on the receiving end of inadequately skilled healthcare providers at improper facilities. They are three times more likely to be denied healthcare and four times more likely to be treated badly by healthcare systems14;

People with a disability are three times more likely to become a victim of sexual, emotional and physical violence. People with intellectual and mental disabilities are the most vulnerable15;

Children with a disability are almost three times more likely to experience sexual violence than their peers without disabilities, and for children with an intellectual disability this is even higher: 4.6 times15;

Between 40 and 68 percent of young women with disabilities and 16 to 30 percent of young men with disabilities experience sexual violence before the age of eighteen16;

Forced sterilisation of women and girls with disabilities happens up to three times more often than amongst their peers17.

All risk factors associated with HIV (poverty, lack of education, lack of SRHR information, higher risk of violence and rape) are higher for individuals with a disability13.

Everybody Matters

Working towards inclusion is not necessarily difficult. On the contrary, existing services can be easily adapted to suit people with disabilities15. Good practices, whereby SRHR and disability inclusion come together, do exist but are rarely documented. This book aims to bring these practices to the forefront, so that barriers can be broken down and bridges can be built between the worlds of SRHR and disability. To Leave No One Behind – an overarching theme in the Sustainable Development Goals18 (SDGs) – in addressing sexual and reproductive health and rights, all stakeholders, including governments, SRH service providers, NGOs, activists, people with disabilities and their parents have an important contribution to make. This can be done most effectively when stakeholders link up with each other and work alongside each other. Together, we can work towards ensuring that the sexual and reproductive health and rights of people with disabilities are fully recognised and addressed, in turn, empowering people with disabilities to make their own decisions about their sexual and family lives.

Read the book here: Everybody Matters: good practices for inclusion of people with disabilities in sexual and reproductive health and rights programmes

In November 2017, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of People with Disabilities, Catalina Devandas Aguilar, was visiting the Netherlands for an expert meeting on disability and sexuality organised by the Dutch Coalition on Disability and Development (DCDD) and Share-Net International, the knowledge platform on sexual and reproductive health and rights. I had the honor to present her the book ‘Everybody Matters: good practices for inclusion of people with disabilities in sexual and reproductive health and rights programmes’, which I authored and edited on behalf of DCDD and Share-Net International.

Activism, intersectional feminism and comedy

Intersectional feminist and disability rights activist Nidhi Goyal from Mumbai, India, raises her voice in all possible ways to promote disability rights and gender justice. She is a trainer, writer, researcher and advocate, from the grassroots to the international level. On top of all her serious work, she performs in her own comedy shows, using the art to perform issue based comedy and raise awareness on disability, gender and sexuality.

“I am Nidhi Goyal and I am blind. Yes, I am blind and so is love: get over it.” That is how Goyal starts her show in a comedy club in Mumbai. In her show, she also shares the reaction of a man who had seen her profile on matrimonial site Shaadi.com. “I remember this one educated, progressive man who called to say I would be perfect for his son, but from what he was saying, I guessed he had not read about my disability. I clarified this with him because it had happened too many times by then. He paused. People generally go into shock, because they do not believe that someone who’s disabled will even be on the website. They can’t connect the picture they’ve conjured up of the well-educated, outgoing girl from the profile with someone who is also visually impaired. So after a few moments of silence, the man said, ‘Really?’ So I repeated myself: ‘Yes, I cannot see. I am blind. Is that okay?’ He said, ‘Yes, no, no, uh, I think uh… ya… good luck,’ before he hung up. That is when I learned disability is indeed contagious: I said I am visually impaired, he became speech impaired!”

Challenging misconceptions

Her shows are about her daily experiences and that of her friends who have a disability, mostly in interaction with non-disabled people. Her performance reveals different layers of how people think about those with disabilities and dating, relationships, sexuality or having children. “It is the small daily conversations that show how deeply prejudice and

stigma are entrenched in society. The misconceptions are not only on asexuality or hypersexuality, but also, for example, that disability breeds disability.”

“Apparently it is indigestible that a woman with a disability is standing on stage, talking about sexuality“

With comedy, Goyal wants people to just sit, listen and enjoy. To listen and learn is easier like this, she thinks, because the audience does not feel targeted directly. After her debut, she received mixed reactions. “One woman came up to me and said: ‘I laughed a lot, but I was also cringing and thinking, oh, yes, I have these misconceptions too.’ She said that it had opened her eyes. On the other hand, I noticed that apparently it is indigestible that a woman with a disability is standing on stage, talking about sexuality. It is a shock for people, as we do not expect that someone with a disability would be funny and could laugh at her disability experiences. When they do not laugh, it is fine, you change your jokes, talk to them: eventually they get it. As I always say, we, people with disabilities, are laughing at the silly, ignorant and prejudiced behaviour that society exhibits. If you do not get it, the ultimate joke is on you.”

Fighting at all levels

When Goyal was 15 years old, she was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, a an incurable irreversible degenerative eye disorder. Within a few years, she would slowly turn blind. Initially then, Goyal had to make some quick career choices since she had dreamt of becoming a portrait painter. Her visual impairment and the gradual loss of eye sight layered her education opportunities, her navigation of an inaccessible city, and social barriers. Her eyesight also began making the difference in interaction with her classmates and college friends. “I was lucky that my parents were very understanding and strong. My father was advised to hide my disability and get me married as soon as I turned 18, because ‘of course’ I would not be able to find someone once I was completely blind, that was the assumption. My father rejected this. This is when I realised how strong the stigma is in society is.

Today, she is fighting against this stigma. Alongside her comedy show, which she performs in India and globally, the spectrum of work that Nidhi Goyal exercises is tremendous. “After my Mass Media studies, I worked as a journalist, writing about women, disabled women in particular, but at one point I decided that this was not enough, I needed to do more. That is how I entered the development sector and the broader field of activism.” Nidhi Goyal works with a range of women’s rights and human rights organisations. She is the program director of the Sexuality and Disability Program at a Mumbai based non-profit, Point of View, where she has researched and co-authored the online platform www.sexualityanddisability.org. This website discusses the sexual rights of women with disabilities, their bodies, sexuality, relationships, marriage, parenting, violence and abuse. Under this program she also conducts trainings for people with disabilities on these topics. Moreover, she is a consultant researcher with Human Rights Watch and has consulted with the feminist human rights organisation CREA on disability policy and international human rights mechanisms. She writes in books, academic journals, news platforms and blogs about her experiences and opinions to raise awareness on issues faced by girls and women with disabilities. Finally, she is on the civil society advisory group of the UN Women’s Executive Director, and takes place in the advisory board of the innovative grant facility VOICE (initiated by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs).

“The interaction with so many people with disability, knowing their stories and contexts, that is what I like the most. I love that I can stand with them, embrace their struggles and fight and raise my voice, and can advocate. I’m very conscious of the privilege that I have in accessing and working with the grassroots as well as the national and international policy arenas. I think I gained this access because I learnt early on in my disability that there are alternate realities, and becauseI really like to work with people within their context. I know it may not be a good idea to go into the interiors of an underdeveloped or developing country to tell people: look, CRPD20 gives you these rights. That makes no sense: who is CRPD? For a woman with a disability living in rural India whofaces isolation, stigma, non-acceptance, and abandonment – in her context, she does not care about human rights or mechanisms. That is a conversation for the policy level.”

Having no dreams is impossible

“Whilst working with a lot of women and girls with disabilities, I have seen that many of them have strongly internalised almost all gendered prejudices including the idea imposed on them by others that they do not have desires, that they do not have the right to dream, and that they are undesirable. They are convinced that no one would ever be with them and that they should be happy with anyone who might ‘want them’. That is what they have heard their entire lives. That is why the first step is to empower them so that they can begin challenging this stigma around them and inside them. During our trainings with Point of View, we realised that women with disabilities are rarely asked to dream. They do not dare to have ambitions in their personal lives. One of the girls said: ‘I have no dreams.’ And I said ‘that is impossible. As a simple example, do you not feel like dressing differently, do you not love a sari?’

‘I would love to wear a sari.’

‘What is stopping you?’

‘Well, because I’m disabled.’

‘But what is the connection?’

‘I do not have functioning body parts from my waist downwards,

why would you wear a sari when you have no legs?’

You see, it is not only a question of sexuality as sex, but also about what you want to wear, who you want to be, how you want others to see you, how to express yourself.” How does change happen? “I think the best way to positively change this issue of disability and sexuality, is to work on raising awareness and to make sure people with disabilities are visible in public spaces in order to get rid of the prevalent stigma. What would also help is positive or ‘normal’ representations in mainstream media including advertisements, films, television, etcetera. At the same time, we must empower people with disabilities to become self-confident and live full lives like anyone else.”

“It is not only a question of sexuality as sex, but also about what you want to wear, who you want to be, how you want others to see you, and how you express yourself”

According to Goyal, one of the gaps to be filled by NGOs and governments is the lack of documentation. “We are invisible because numbers are invisible, our issues are invisible, and research is, to a large extent, invisible. That starts a cycle of invisibility and suppression and a neglect of rights. Disability inclusion should be measured at many different levels: in accessibility, in comprehensive sexuality education, and in health services.”

The purpose is not to stick to disability related spaces, or research journals, for a one-time engagement. “Disability should be seen as a cross-cutting issue with many other identities and issues. So, for example, if a sexual rights or health journal comes out with one special issue on disability and encourages research it would be a great first step. But in the long run, disability research needs to become a part of health, reproductive rights, sexual rights researches and discourses. We need to open up spaces and make them more inclusive rather than, for example, having that one panel of marginalised voices in a women’s rights or sexual rights conference. Similarly, all plans, policies and programs at national or global levels need to consider and include disability rather than only having a separate law or policy for people with disabilities. That would be real inclusion.”

Is there already progress? Yes, “Small efforts are already going well. However, they are not yet visible enough and the various ‘efforts’ are not working together or in synchronicity. Organisations with different expertise, engaged in disability rights and sexuality rights, should join forces. Disability rights groups may not have a clear understanding of sexuality and what it means. They have often internalised the stigma around sexuality and certainly around gender. They need to talk with sexuality rights groups. They need to open up and talk and start a movement or a collective of some sort, to engage in and gain an understanding of what sexuality is. In conservative regions in particular, it will be important to first change the prevalent misconceptions of sexuality in the disability-rights groups and coalitions themselves. At the same time, the issues of girls and women with disabilities should be led by disabled women and not by their male counterparts. Similarly,

organisations working on sexual and reproductive health and rights should deal with their prejudices and work together with disability groups to be sensitised and to eventually become inclusive.”

A rising flame

Although Goyal is mostly working with women and girls with disabilities, men and boys face difficulties and stigma, too. “For men and boys, their masculinity and power is automatically assumed by patriarchal society, but for those males with a disability, this is not necessarily the case: often, their masculinity and power is threatened and they are perceived as ‘not man enough’. Therefore, in trainings, advocacy or campaigns on disability and sexuality we cannot leave out gender and identity.”

Goyal is now expanding her work. In September 2017, she launched her organisation ‘Rising Flame’. “I want people with disabilities to find their voice, rise for their rights, become self-advocates and leaders who embody the change they want to see. Through our various programs we will use technology, arts, networks, mentoring and social access and support to build an inclusive world where diverse bodies and minds can live with dignity.”

“My dream is that intersectionality becomes a concept that people and societies understand effortlessly, where multiple power structures are broken down, where all the movements are converging and working with each other: the women’s movement and the disability movement. In the meantime, I keep working on the intersection of these, negotiating, pushing, and rising for my rights and rights of people with disabilities.”

Drawings by De Beeldvormers

Veldonderzoek in Nepal

In april en mei deed ik voor Karuna Foundation kwalitatief onderzoek in een klein plattelandsdorpje in het zuidoosten van Nepal: wat maakte het Inspire2Care programma van Karuna al dan niet succesvol, volgens de lokale bevolking? Hoe kijken dorpsbewoners naar mensen met een beperking en hoe is dat veranderd? Enkele foto’s. Een uitgebreider verslag volgt binnenkort!

Cuban imaginations of the future

Havana is full of small businesses. The most common entrepreneurs are ladies who sell cupcakes and cookies from their front door or window, small cafeterias with coffee and a sandwich for some pesos, people selling the latest American movies and series on copied DVDs, and men walking with carts and shouting in a special loud and low tone that many of them use: “Tengo galletas de mantequillaaaaaaaaaa” (I have butter cookies). When there are eggs and/or potatoes – products that are scarce – that is shouted loudly: “Hay papa, hay huevo, hay papa, hay huevo” (there are potatoes, there are eggs). It is almost like a song, or maybe a rap. Together with the roaring engines of vintage cars, and an occasional rumba or reggaeton beat, it forms a cacophony that is typical for the neighborhood.

Havana is full of small businesses. The most common entrepreneurs are ladies who sell cupcakes and cookies from their front door or window, small cafeterias with coffee and a sandwich for some pesos, people selling the latest American movies and series on copied DVDs, and men walking with carts and shouting in a special loud and low tone that many of them use: “Tengo galletas de mantequillaaaaaaaaaa” (I have butter cookies). When there are eggs and/or potatoes – products that are scarce – that is shouted loudly: “Hay papa, hay huevo, hay papa, hay huevo” (there are potatoes, there are eggs). It is almost like a song, or maybe a rap. Together with the roaring engines of vintage cars, and an occasional rumba or reggaeton beat, it forms a cacophony that is typical for the neighborhood.

This cacophony of the street has not always been like it is now. Cuba is in a transition that went from frozen contacts with the United States and a travel and trade embargo since the 1960s to tourist flows and the visit of Obama in 2016; from prohibitions on internet and foreign media and (rock) music to open WiFi-parks and a Rolling Stones concert attended by supposedly half a million people; from socialist labor perceptions and practices of work, in which entrepreneurship was forbidden, to a more open and free landscape with room for self-employment and an adapting working culture; and from politicians seeing as an evil, only necessary to save the Cuban economy from collapsing, to them viewing it as a building stone to even perfect socialism (1).

Ever since Obama and Castro shook hands, Cuba has been a hot item in media worldwide. In general, journalists write in the line of thought that the island is becoming capitalist, and will soon be flooded with franchises of Starbucks and McDonalds. Likewise, tourists are urged (2) to go to Cuba before it loses its ‘authenticity’ (whatever that may mean). In this mostly Western view, entrepreneurs are seen as the key agents who push Cuba towards a free market society. But how do they themselves perceive this role? How do they experience the Cuban transition? And how do they see their own and Cuba’s future?

In the early 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Cuban economy came in an abrupt crisis due to a high dependency on the Soviet bloc. The Cuban government was confronted with urgent needs for reform: opening up to foreign investments, increasing efficiency and productivity, and… giving space to new small entrepreneurs. In 1993 it became permitted to start a private business, but only in a limited number of professions. In 2010 the government announced new guidelines for entrepreneurs. Self-employment was totally abolished after 1959 and the regulation from 1993 that legalized non-state enterprises was mostly a necessary anti-crisis evil. Now they were supposed to save the economy and peculiarly even appointed to strengthen the revolution. But becoming a capitalist country…?

I found out that Cuban entrepreneurs themselves do not experience a transition from socialism to capitalism, or to put in similarly dichotomous terms: from dictatorship to democracy, from micro-state monitoring to freedom. Entrepreneurs mainly experience a transition between two different working cultures: an old ‘revolutionary’ one with business activities limited to the thriving black market, and a new ‘entrepreneurial’ one with blooming small business and strong entrepreneurs, well adapted to the new policies. Whereas policies are easily changed, the ‘slowness of culture’, as Ton Salman (3) calls it, makes that people’s mindsets and habits stay behind. Culture takes its time to adapt. And the decades of state socialism logically have their impact on the Cuban culture, which we could view as a consequence of governmentality (4).

To discuss Cuba’s future with my informants in terms of socialism versus capitalism appeared inevitable, but this does not mean that Cubans agree with the in the West envisioned capitalist future for Cuba. I heard very different opinions, varying from “Socialism? That is long gone in Cuba” to “We will not become capitalist, but remain on the revolutionary path.” Overall, most Cubans do not see a future for capitalism in Cuba but they find it important to take some of the good aspects, for example more freedom. Most Cubans do derive hope from the recent Cuba-US rapprochement that their country is going to improve economically and some even are preparing for opening businesses when the relations are fully recovered. Apparently, Cubans also have no straightforward answer to what Cuba’s political-economic future contains, which shows diversity and heterogeneity.

The transition is obviously still ongoing and this means that a lot is yet about to change for cuentapropistas. Three days after Obama left Havana and I was waiting for the Rolling Stones concert to begin, I felt the significance of my research more than ever. Everyone around me said it was a historical week that marked the changes that are going on in Cuba. But it remains important to keep in mind that Cuba’s evolving future might take several and unprecedented directions instead of holding on to the ‘evolutionist’ idea that the only possible end goal for Cuba is capitalism as we know it.

I wrote this blog for the platform of my faculty, Social and Cultural Anthropology at VU University: http://www.standplaatswereld.nl

Sprucing up Havana for some special guests

Now, it is all over. I went to Cuba, wrote my MA thesis, and in July received an email that I graduated. It sounds so simple, and quick. Yet when I look through my pictures or lay down in the park (I finally have time for that), I recall some of the great moments. I will share some of them here.

For once I do not smell the pollution of the vintage cars when I cross the street in front of Hotel Capri, because the smell of fresh asphalt is even stronger. We are close to the United States Embassy. The sound of drilling machines hurts my ears. Drips of paint are falling down from above; the facades and balconies are rapidly (but not so carefully) given a fresh color. Park benches and fences too. Suddenly the usual garbage on the street corner is gone. And everyone knows: Obama will pass here, in this street!

During Obama’s visit from Sunday to Tuesday, important government services will be shut down; banks and exchange offices, the Cuban telecommunications store ETECSA and all the museums are closed, just like many important roads. “The next few days are complicated. Watch yourself, and do not plan important meetings for which you need public transport”, I was warned several times. “It is always like this, when anything important happens”, my landlady explains.

I could feel the city’s exciting vibes. The conversations between thrilled Cubans in the stores, at the market, and in the waiting lines were about nothing else in the last few weeks. It was a week that was supposed to become a ‘turning point’ in Cuba’s history, and it put the island in the spotlight of the global media. This and another great event made my final week of fieldwork in Cuba historical: three days after Barrack Obama visited the country as the first United States president in 88 years, the Rolling Stones gave a free concert in the Ciudad Deportiva of Havana, attended by supposedly half a million people. And I think about that moment…

I am standing on a field in the Ciudad Deportiva of Havana with my roommate Rochelle and thousands and thousands of people, the sun burning on our skin. The first big rock concert in Havana by the Rolling Stones is considered historical. The stage is only about ten meters in front of us, as Rochelle and I were among those who were waiting already all day, to start sprinting hand-in-hand at exactly two o’clock in the afternoon, avoiding gates fallen down at the grass. Cuban fans brought their beloved arroz con frijoles (rice and beans) in large buckets for lunch and dinner. It is now about 8.30 pm and people are sweaty before the concert even started. A 42-yeard old Cuban man next to me talks and talks, thrilled and obviously a huge fan, about how much he loves the Rolling Stones. In the middle of a sentence, he suddenly stops and waves my question away; just at the moment that Keith Richard plays the first notes on his electric guitar on Cuban soil.

“Aquí estamos finalmente” (Here we are, finally) says Mick Jagger just after the opening song Jumping Jack Flash. And later: “We know that earlier it was difficult for you to listen to our music, but I guess times are changing, aren’t they?” Whereas everyone around us is screaming, singing and jumping, the man next to me is silent and I see him wiping away tears from his face. “After this day, I may die”, he tells me emotionally. “It is unbelievable that I may experience this. You probably cannot understand, as you could already see the Rolling Stones before, but for me, this is like…I don’t know… the first time I have sex, something like that. It is legendary. Finally Cuba is changing.” The crowd bawls and the huge screens show waving United States and Cuban flags, actually, all the flags of the world.

And I think about what one of my informants, Camilo, had said earlier, answering the question whether many Cubans indeed want to leave the island: “I want to stay in my Cuba, of course! I want to be there at the Grand Moment of History. That is, when everyone acknowledges… that a change is possible in this country.” Maybe this week was already that point in history, as Camilo foresaw, that Cubans recognised that things are changing and about to change even more in Cuba. This final week in Havana made very clear to me that people are not only and always thinking economically. Cubans are proud of their country and culture. At this moment of rock-grandeur, maybe this pride is even more important than improving the economy (a goal that is often emphasized by the Western media) or leaving the island to live a ‘better life’. What a great experience my final week on Cuba was!

See the original blog on StandplaatsWereld, the VU University blog platform of the Department of Anthropology.

Cuba: A new working culture?

Cubans are friendly, helpful, and welcoming. Until you enter a public service building such as a bank or a state-run store, or restaurant. Why is that? An exerpt from my fieldnotes.

In the middle of the city center, just next to the Capitol and in front of ‘El Parque Central’, I find Hotel Inglaterra, one of the most luxurious hotels in town, next to Hotel Parque Central, Hotel Nacional, and Capri, and Havana Libre. In this hotel they have Wi-Fi, and whereas tourists use their smartphones while nipping their cappuccino on the terrace of the hotel, Cubans stand outside against the wall, the Wi-Fi reaches just far enough for them, too. I also use it for that.

In contrast with the beauty and luxury of the hotel, and the relatively high prices, the service is horrible (yes, that are my own terms). There is only one waiter for the whole terrace, sometimes two; one for each side. But no one comes to ask you if you want to order anything, you have to call them yourself, and that costs some time and patience. If you have ordered, it can easily take half an hour before you get a drink. If you ordered food, you could wait for an hour, and then in between I have asked a few times how long it takes. When you finally get your food, you find out the drinks are lacking, and after asking that again, it takes another 15 minutes.

When you order, the waiter just looks at you, not even with a smile. After ordering, he just walks away. Also no words are used to bring you the food, he looks around while doing it. If something is not there, and that is even the case in luxury restaurants and hotels, you hear a short ‘no hay’ and nothing further.

I was told before that the service in state-run hotels or restaurants is really low, and that could be explained by the fact that for generations, Cubans are not used to work harder, try to be nice to customers, because they did not get paid any more for doing that. They also do not get fired for not doing it. That is why I heard, before I got here, that the service is mostly better in paladares (private run restaurants) or cafeterias. However, also in those places I found the people not nice, and they did not work efficiently either.

But this does not only count for restaurants. Also in stores, no matter state-run, run by cooperatives, or cuentapropistas, people are short, do not make effort to help you further if something is not there (no hay!), refuse to explain why something is as it is, and cannot tell you when something will be available (no sé). People do not really smile either, unfortunately.

I can imagine that if you do not have any incentive to work efficiently or to be friendly to people (which, I find, is an incentive of life itself rather than a money incentive, but not for all people, obviously), it is difficult to just change that, even if now money IS involved and you DO get higher profit by trying harder. So the money-explanation is not accurate. It may be an incorporated, cultural, and social thing, that is thus not easily explained, nor changed.

This thought was enforced when this week I talked to a professor of FLACSO (Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences) who investigated micro-entrepreneurs himself, and who also runs a cafeteria on the side, together with his parents. Leonardo told me that exactly because Cubans are not used to work harder, because they earn the same money anyway, they do not have any motivation for being nice to customers. But even if they do have this money motive, it is a habit that is so much incorporated that it became a cultural aspect that is hard to change at once, by just adding the money incentive to their work. He said it probably takes a whole generation to change this attitude.

It may be interesting for me to research this phenomenon more closely. I could link it to philosopher Foucault’s concept of governmentality: a certain system that is introduced by a powerful institute (in this case the Cuban socialist state), makes that people start to act and think in a certain way. A term that fits well in this concept is embodyment. It is, however, a bit different than the classical form of governmentality; they are taught and raised to think in line with socialism, which makes them believe in the system even in an unconscious way. But this lacks the acknowledgement that Cubans have agency and presumes that they are only ‘brainwashed’ by this system. So nuance is necessary here.In my thesis I will keep reflecting on this and cultural difference. Because: what does this tell me about my own assumptions and their influence on my fieldwork?

Cubaanse ondernemers in beeld

Vanaf eind december tot en met eind maart was ik drie maanden in Havana voor mijn veldonderzoek onder Cubaanse ondernemers, over de Cubaanse transitie, strubbelingen, oplossingen en hun toekomstbeeld en -dromen. Momenteel schrijf ik hierover mijn thesis voor de master Social and Cultural Anthropology. Een inkijkje in een prachtige, complexe, niet-volledig-vast-te-leggen stad.

Indrukken van Havana

“31 decemeber is een complexe dag”, had ik al twee dagen van tevoren gehoord. Winkels zijn vroeg gesloten, maar je weet niet hoe laat precies. Transport door de stad is moeilijk, aangezien iedereen, todo el mundo, inclusief taxi- en buschauffeurs, de late middag en avond bij familie doorbrengt. Dus vertrek ik om drie uur vanaf mijn huis in Centro Habana richting San Miguel de Padrón, waar de Cubaanse Alex – die in Nederland woont en studeert – en zijn familie me bij hen thuis uitgenodigd hebben om oud en nieuw te vieren. Alweer twee weken geleden maakte ik voor het eerst kennis met het Cubaanse taxisysteem.

Ik kijk wat onwennig om me heen, het is pas mijn derde dag in Havana en ik bevind me op nog onbekend terrein. Op zoek naar een taxi. Vanaf Parque Curita zouden er taxi’s naar de buitenwijk San Miguel de Padrón moeten vertrekken. Het park is meer een soort plein en rotonde ineen, een grote chaos. Ik zoek een bordje, maar dat is nergens te bekennen. Wel vind ik een groep mensen mensen die lijken te wachten. Ik vraag aan de man voor me in de rij waar ik moet gaan staan om richting San Fransisco, te gaan. Mijn Spaans is nog niet top, en het Spaans van de Cubanen is vooral snel, en ze spreken veel letters niet uit. San Fransisco wordt bijvoorbeeld Sa Fra-i-o. Het duurt dus even voor ik, gedeeltelijk, begrijp wat hij zegt. Maar de man is geduldig en helpt me, wanneer de volgende auto aankomt, door me naar voren te duwen, de chauffeur te vragen waar hij heen gaat, en me op de voorbank naast een ander meisje te proppen.

Waar we in Nederland lekker met zijn allen in de file staan, in elke auto vaak maar één persoon, stoppen ze hier alle auto’s vol met mensen die dezelfde kant op moeten. Daar houdt de efficiëntie echter wel op. Er zijn verschillende vaste routes, en alle Cubanen lijken die te kennen, maar het staat nergens opgeschreven. Als nieuwe buitenlander moet je dus gerichte instructies hebben of je suf rondvragen op straat. Als er mensen aan de kant van de weg stil staan en hun hand uitsteken, weet je dat je in ieder geval op de route zit. (Als het echter een wat grotere groep is, wachten ze vaak op een bus.) Alleen weet je nog niet welke kant de auto’s op gaan: ze hebben geen bordje voorop met de route, dus stoppen ze allemaal bij elke persoon die het lift-teken gebruikt, en rijden ze weer door wanneer die ergens anders heen wil. Een bordje zou zo simpel zijn. Voor 80 cent rijd je 20 minuten naar een ander stadsdeel. Deze taxi’s zelf zijn de meest charmante, maar oudste, meest verroeste en hardst rammelende Amerikaanse oldtimers die er zijn, in tegenstelling tot de glimmende cabrio’s met vlaggetjes die voornamelijk toeristen vervoeren voor een veelvoud van de prijs.

Mijn auto richting San Fransisco, een lichtblauwe met mooie rondingen, racet rammelend door de niet zo drukke straten, slingerend om de grote gaten en hobbels in de weg te ontwijken. Het bruine leer met geruit stiksel dat de hele binnenkant bedekt, is afgebladderd, en bijna niks op het dashboard lijkt te werken. De stank van uitlaatgassen dringt door het raam naar binnen. Wat dat betreft fijn dat er niet zó veel auto’s zijn, dat is voor de meeste Cubanen onbetaalbaar.

Met hakkelende reggaeton op de achtergrond – de radio werkt niet goed – razen we voorbij de vervallen maar op een bepaalde manier toch prachtige architectuur van het oude Cuba, elke pilaar en elk kozijn in een andere felle kleur geschilderd. Samen met die heerlijke antieke auto’s een stad naar mijn hart wat dat betreft, dan is Nederland maar grijs en saai. Op de achterbank wordt gezellig geschreeuwd, ik versta er niks van maar het klinkt vrolijk. Langzaamaan komt er steeds meer ruimte voor tuintjes en bomen aan de kant van de weg. Hoe verder we komen hoe kleiner en slechter de huizen eruit zien. Na twintig minuten ben ik bij mijn bestemming: de Etecsa (het telecommunicatie-bedrijf van Cuba) in de wijk La Cumbre. Ik reken 80 cent af en kom tot de conclusie dat dit taxisysteem geniaal is: na even uitzoeken blijkt het snel, makkelijk en goedkoop. En je maakt nog eens een praatje onderweg. Ik ben er meteen weg van!

Vanavond tijdens het avondeten in mijn nieuwe casa vertelde mijn Italiaanse huisgenoot me dat het taxisysteem ook verder strekt dan deze auto’s. Voor grote afstanden, tussen steden, is de goedkoopste manier om een van de camiones te nemen, eigenlijk gewoon vrachtwagens die eerder op dierenvervoer schijnen te lijken, die ze volproppen met reizende Cubanen. Het is legaal, maar het aantal mensen dat vervoerd wordt zéker niet. Kan nog interessant zijn voor mijn onderzoek.

Doing research in Cuba: ‘You could be a spy!’

I was still a naive foreigner and a naive researcher by the way, when I explained to Alex – a Cuban friend that lives in the Netherlands since he was eleven – that I was looking for stories that exposed the way Cuban entrepreneurs participate in the ‘informal economy’ to solve their daily problems, the creative ways they meander around the rules, and their view of Cuba’s future. When we were celebrating newyears eve in the back yard of his family’s home, while enjoying cheese and beers and the smell of pork from the barbecue, Alex helped me directly and translated this in a private conversation with his step-father, whom he considered to be a potential informant for me.

In first instance, his father agreed to help me, but when Alex explained what exactly it was that I was looking for, still focusing in my formulation on ‘resistance’, ‘creative ways to use or meander around the rules’ to ‘expand their leeway’, he was kind of shocked. He told Alex (who told me later) that people are not eager to talk about that, and that although everybody does it, and everybody knows it, no one is talking about it. On top of that, I could be a spy! And the thought of that possibility only leaves their minds when the opposite is proven; they are ‘obliged’ to not trust foreigners. Ironically, of course, proving I am not a spy is impossible. Moreover, a true communist will just report me, and that is not only dangerous to me, but even more dangerous to my informants and even anyone I spoke to.

I was already made aware by several people before that I should be careful with my subject, but this felt like a slap in the face. The facts directly got to me on my third day in Havana. However, facts… maybe the actual risks are not that high of being caught by the government, but obviously the risk is experienced by some, and therefore it is important anyway.

I heard it more often, that Cubans will not generally talk about political issues, or about forms of resistance, but this experience really got me a bit scared that I would never find the information that I was looking for. Note to self: rewrite research questions and never again explain my research again the way I did!

Musing high in the sky

I look at my new diary, received from my mother-in-law. It’s the perfect diary. The cover is a colorful spectacle, with golden light balls and red, green and blue peacocks’ eyes, that change into leafs, in between. With some fantasy one could see different things, but it reminds me of citylights and traffic, mixed with a peaceful park maybe. Clearly bored at the airplaine, I think to myself that it is a symbol of my fieldwork as I now expect it to be: mysterious, vague but beautiful, especially when you see the full shining picture. Things you see could mean different things, but I will interpret them in a certain way. Boundaries are not always visible, they could be blurred or moving.

I am on my way to Havana to do anthropological fieldwork for three months for the purpose of my Master thesis. Although I have read pages and pages and spoke to several people beforehand, Cuba is a great mystery to me. In the past few months, when I dived into literature and spoke to people who already know the country from different perspectives, I often felt confused. Everyone says something else. One could say the country is beautiful and rich of culture and ideology, or one could say it is poor and citizens are crying for more freedom and access to material goods. Or both. One could say the people are incredibly creative when dealing with scarcity and state rules, or they could be described as lazy, not wanting to work harder for they still gain the same income of the state when they would. Or again: both. One could say everything is changing fast since Raul Castro got in power in 2008, opening up opportunities for people, especially cuentapropistas (entrepreneurs) and foreign traders, or one could argue the changes are not profound enough and politics slow down necessary economic change. I do not know. And I regret to say it but I think I will not know it either, since Cuba is ‘a complex case’ according to different scholars, ánd the Lonely Planet.

In my imagination, the country must be beautiful, nostalgic and heroic, full of music and nice and tolerant people who are used to take care of each other. But I have also read about the island as being more and more materialistic, with a (to me) new kind of inequality, and furthermore ambiguous and vague. Lines of legality are blurred into some kind of illegality or creative legality. It is within this ambiguous leeway that entrepreneurs, my focus group, need to maneuver. This is what attracts my attention and interest. This is what I will dive into and focus on during the coming three months of ethnografic fieldwork. I hope to learn to understand how Cubans deal with a changing policy landscape and maybe even changing ideologies. I want to know they experience and interpret their leeway of action within the (vague?) boundaries of the Cuban state. And: how Cuban entrepreneurs imagine their own future, and that of their country.

I keep musing, thinking, daydreaming about what those questions involve, how I will do, and how Cubans will react, and in the meantime the sun warms my left cheek. Another plane just crossed our route a few hundred meters underneath us. I can still see the white line the plane leaves in the sky. A Spanish stewardess in Air Europa outfit walks by with beverages, but I already bought a liter of water at Schiphol Airport. In an hour or so I will get off in Madrid, and continue my journey to la Habana, where Marta (changed name) will pick me up at the airport. It is hot and my legs miss some space, but nevertheless the flight is fine. I will need to get used to high temperatures again.

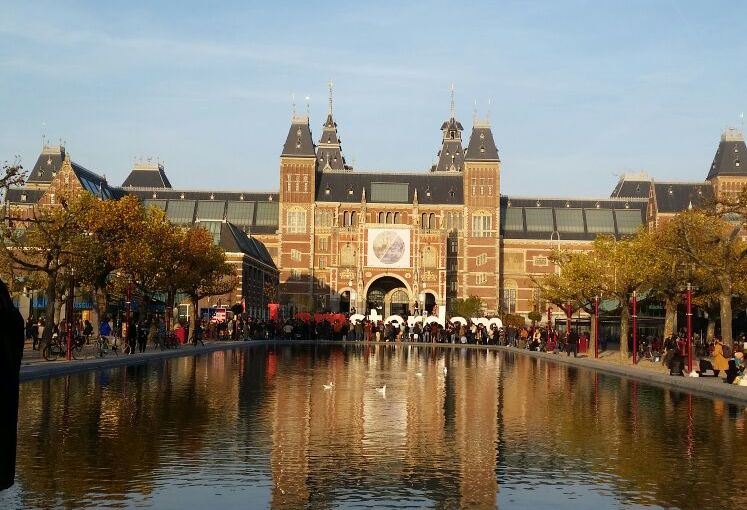

Een rondje Rijksmuseum en de gevolgen van koloniale geschiedschrijving

MASTER ANTROPOLOGIE – Ik loop door het Rijksmuseum, wandel door de gangen met 17e-eeuwse kunst en koloniale geschiedenis van Nederland. Ik bewonder een reconstructie van een groot VOC-schip en de portretten van de helden die de Nederlanders roem en rijkdom brachten eromheen. Teksten op de muren beschrijven de Gouden Eeuw, met zijn slimme koopmannen en handelaren, zeehelden en de gevechten tegen andere koloniale machten voor zilver en specerijen. Er bekruipt me een ongemakkelijk gevoel. De andere kant van het verhaal, de zwarte pagina’s uit diezelfde geschiedenis worden weggelaten: slavernij, uitbuiting, landroof en zelfs massamoord. Wat zegt deze manier van geschiedschrijving over ons, en wat zijn daar nu nog de gevolgen van?

Onderstaand essay schreef ik als onderdeel van de master Sociale en Culturele Antropologie.

A walk in the Rijksmuseum

The reframing of colonial history and its implications

I walk through the 17th century department of the Dutch national art and history museum, the Rijksmuseum. It shows an immense wooden ship on which the VOC (the Dutch East India Company) sailed to what is now called Indonesia. The portraits of the heroes who brought colonial wealth to the Netherlands hang around it. As I walk past the writings on the walls telling about the Golden Age, with its heroes of the sea, battling against other colonial powers, and about smart merchants and traders, a feeling of awkwardness comes over me. It makes Dutch people proud of their history, which brought them so much fame and wealth at the time. But the other side of the story, about the black pages of Dutch colonial history, that tell about slave trade, exploitation, acquisition of land, and even mass murder, are merely neglected.

This museum visit – a few weeks ago –popped into my mind while learning about the (lack of) recognition of cultural wounding (Kearney 2014) and the suffering of indigenous peoples and slaves. In this essay I will focus on the importance of recognition by former colonial governments of the harm done to indigenous peoples, slaves, and their descendants. I use the concepts of governmentality and cultural wounding and healing to analyse the implications of how former colonial powers nowadays delineate their pasts.

Denial, governmentality, and cultural wounding

My experience in the Rijksmuseum seems similar to Ödzil’s (2014) in the Mauritshuis, another relic of the Dutch colonial time, turned into a museum. He states that in this museum, too, there is a lack of attention to the involvement in slave trade of ‘hero’ Johan Maurits, who was the governor-general of Dutch Brazil, which was colonized by the Dutch Republic between 1630 and 1654 (Ödzil 2014:52). In addition, he cites Weiner (2014) about the current history books of children about the colonial time:

Dutch textbooks ‘obscure and distort the Netherlands’ role in enslaving Africans [and] justify their history of colonialism, exploitation, oppression and genocide for profit and labor […] Furthermore, they racialize White Dutch as largely uninvolved with the dehumanization and exploitation of Africans but as good traders, or businessmen […]’ (Weiner 2014:16-17, cited in Ödzil 2014:51). Ödzil uses the metaphor of ‘pasteurization’: the systematic underplaying of the role of the Dutch during slave-trade periods, ‘to not upset’ the Dutch public (2014:50-51).

Similarly, the Australian government mediates the Australian colonial era as a great and a merely positive “contribution to the Australian ethos and character, denying the depth of suffering and wounding experienced by Indigenous people […]” (Kearney 2014:608). Kearney argues that by not recognizing, in historical accounts, the indigenous peoples’ cultural wound of the colonial land acquisition, genocide, loss of social structures and way of life (among other things), achieved even further wounding of many indigenous Australians (ibid:608).